‘Los días de la ballena’: resistance in Medellín through public space

Within the framework of the IndieBo film festival in Bogotá, this Medellín film about the city, art and resistance was presented. Here some impressions

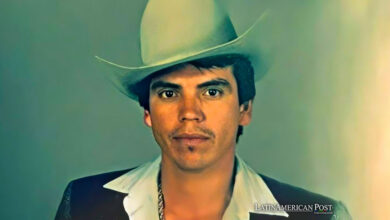

LatinAmerican Post | Juan Gabriel Bocanegra

Listen to this article

“In streets, whoever does not adapt we have to adapt it, and you are very maladaptive,” says one of the neighborhood thugs, who was Simon's (one of the main characters) school friend. The reason: together with his group of friends, especially Cris, the other main character of the film, are graffiti artists and have scratched one of the walls of the neighborhood.

Leer en español: 'Los días de la ballena': resistir en Medellín desde el espacio público

“It's the story of two teenage friends who, a little drunk with rebellion and with that force that gives them their youth, begin to face a criminal gang in a neighborhood. And what begins to be like a game ends up being an experience that changes their friendship and their life,” says Catalina Arroyave, the director of the film, in an interview with the Cinéfila Corporation of Medellín. And yes, it is a story of resistance to social dynamics where public space, in the absence of government authorities, is controlled by criminal gangs.

It premiered at the Cartagena International Film Festival (FICCI) and was also at the SXSW and the Austin festival. In the next six months, they expect to go to other festivals in Europe, as producer Jaime Guerrero said during the IndieBo festival in Bogotá.

Co-produced by Mad Love and Rare Audiovisual Collective, Los días de la Ballena is a film about youth in an overwhelming city that does not listen to them, so they decide to take it their way.

You may be interested: Cinema comes as a resistance tool for women

Resistance and resilience

Cris and Simón spend it on the street riding bicycles, scratching the walls, talking about art; they come to their homes only to sleep or talk to their parents. They try to find their space in the city by inhabiting public places, either under a bridge, in a park or on a street in a neighborhood in the communes of Medellín.

However, the city is not always kind to them, it poses dangers and a constant struggle with other people who believe they own the place. "Toads die by mouth," the thugs write on the wall in front of La Selva, an abandoned house in a dangerous neighborhood of the city after they distributed fanzines in which they denounced the collection of vaccines in the neighborhood.

Despite the fear, they don't give up: they paint the wall white and start painting a whale. “The whale is a metaphor for what Medellín does not see, for what one does not want to look at, for what people learn to dodge. We have this huge problem and there it is, but we no longer notice it,” says Arroyave in an interview with El Espectador about the whale that swims first and then dying in a half of a street in some fragments of the feature film.

Although the whale lies dead at the intersection of the Oriental Avenue with La Playa, it relives in the graffiti that Cris and Simon on the wall in front of La Selva. “The whale is dying because something starts to die in the characters. It begins to die when one grows up, but revives with art”, concludes Arroyave.

Music is also a central aspect of the story. As a sample of what is happening in the city at the musical level, rap accompanies the characters in their wanderings. “One of my platonic loves is music. Perhaps that is why it was one of the most relevant elements of the story since the film was conceived, I always dreamed it as an essential part of the spirit of what I was telling,” Arroyave confesses in an interview with Radionica.

There are songs of Doble Porción, Mañas, Granuja, and Alkolirykos. Of the last group, one of his singers, Castro, acts as one of the artists who direct La Selva.

The film not only shows what happens in Medellin within the film but is also the result of the film boom in the city, with new filmmakers such as Laura Mora or Arroyave itself. The director told Rolling Stone that “in Medellín, we understood that if we don't get together, that if we are not complicit with each other, we will not be able to do what we dream. That is, creating collectively, makes films strengthen as individuals who are networked, who transform into a family.”

As the characters in the movie come together to resist, in Medellín the filmmakers are coming together to give strength to the city's cinema.